Leapfrog integration

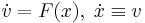

Leapfrog integration is a simple method for numerically integrating differential equations of the form

,

,

or equivalently of the form

,

,

particularly in the case of a dynamical system of classical mechanics. Such problems often take the form

,

,

with energy function

,

,

where V is the potential energy of the system. The method is known by different names in different disciplines. In particular, it is similar to the Velocity Verlet method, which is a variant of Verlet integration. Leapfrog integration is equivalent to updating positions  and velocities

and velocities  at interleaved time points, staggered in such a way that they 'leapfrog' over each other. For example, the position is updated at integer time steps and the velocity is updated at integer-plus-a-half time steps.

at interleaved time points, staggered in such a way that they 'leapfrog' over each other. For example, the position is updated at integer time steps and the velocity is updated at integer-plus-a-half time steps.

Leapfrog integration is a second order method, in contrast to Euler integration, which is only first order, yet requires the same number of function evaluations per step. Unlike Euler integration, it is stable for oscillatory motion, as long as the time-step,  [1].

[1].

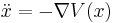

In leapfrog integration, the equations for updating position and velocity are

where  is position at step

is position at step  ,

,  is the velocity, or first derivative of

is the velocity, or first derivative of  , at step

, at step  ,

,  is the acceleration, or second derivative of

is the acceleration, or second derivative of  , at step

, at step  and

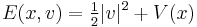

and  is the size of each time step. These equations can be expressed in a form which gives velocity at integer steps as[2]

is the size of each time step. These equations can be expressed in a form which gives velocity at integer steps as[2]

One use of this equation is in gravity simulations, since in that case the acceleration depends only on the positions of the gravitating masses, although higher order integrators (such as Runge–Kutta methods) are more frequently used.

There are two primary strengths to Leapfrog integration when applied to mechanics problems. The first is the time-reversibility of the Leapfrog method. One can integrate forward n steps, and then reverse the direction of integration and integrate backwards n steps to arrive at the same starting position. The second strength of Leapfrog integration is its symplectic nature, which implies that it conserves the (slightly modified) energy of dynamical systems. This is especially useful when computing orbital dynamics, as other integration schemes, such as the Runge-Kutta method, do not conserve energy and allow the system to drift substantially over time.

Because of its time-reversibility, and because it is a symplectic integrator, leapfrog integration is also used in Hamiltonian Monte Carlo, a method for drawing random samples from a probability distribution whose overall normalization is unknown.[3]

See also

- Numerical ordinary differential equations

- Euler integration

- Verlet integration

- Runge–Kutta integration

References

- ^ The Leap-Frog Method

- ^ 4.1 Two Ways to Write the Leapfrog

- ^ Bishop, Christopher (2006). Pattern Recognition and Machine Learning. New York: Springer-Verlag. pp. 548-554. ISBN 978-0387-31073-2.

External Links

- The Leapfrog Integrator, Drexel University Physics

![\begin{align}

x_i &= x_{i-1} %2B v_{i-1/2}\, \Delta t , \\[0.4em]

a_i &= F(x_i) \\[0.4em]

v_{i%2B1/2} &= v_{i-1/2} %2B a_{i}\, \Delta t ,

\end{align}](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/586d8b150ccc42f96ea73130206ee1e1.png)

![\begin{align}

x_{i%2B1} &= x_i %2B v_i\, \Delta t %2B \tfrac{1}{2}\,a_i\, \Delta t^{\,2} , \\[0.4em]

v_{i%2B1} &= v_i %2B \tfrac{1}{2}\,(a_i %2B a_{i%2B1})\,\Delta t .

\end{align}](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/baa8c35e61e2cfc01fdc1078885d3aba.png)